Re-Inventing Judy Rhines

August 20, 2025

By Peter Littlefield

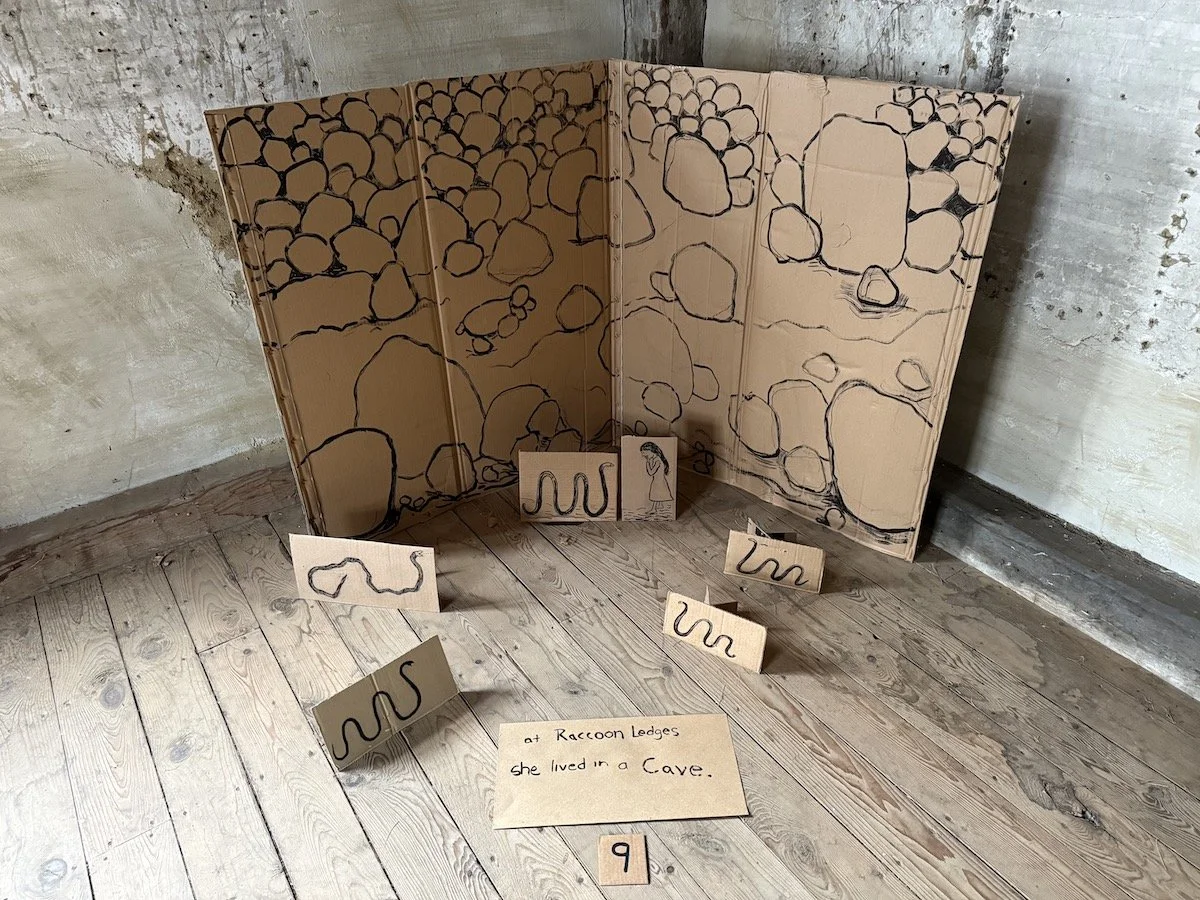

Soon to open at the White-Ellery House on the Cape Ann Museum Green, will be an installation, The Resurrection of Judy Rhines, co-created by artist Gabrielle Barzaghi and myself. Gabrielle drew some 20 dioramas on cardboard in which Judy Rhines – a legendary figure in Gloucester lore – goes walkabout in the Dogtown woods. We worked out the narrative together with the drawings set up as a tour. This is our second Dogtown project, and with this article, we want to describe how our collaboration developed.

First Dogtown Impressions

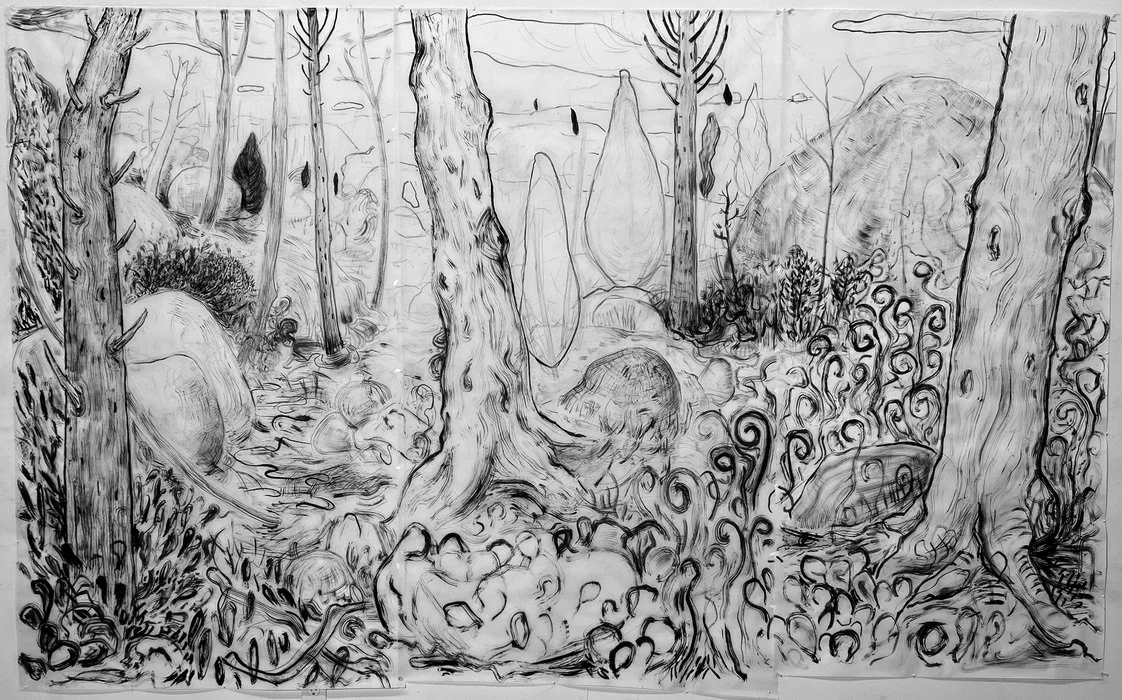

Drawings by Gabrielle Barzaghi, from The Resurrection of Judy Rhines.

Dogtown has fascination for both of us. Gabrielle lives in the Dogtown woods herself, and she's explored their flora and fauna in intimate detail. Growing up on Cape Ann, I heard that Dogtown didn't belong to anybody. Its land was “untitled.” I hoped to run into the hippies that camped out there, but no luck. And then there was the strange collection of outsiders who found a home in Dogtown sometime in the legendary past: Old Ruth, a Black woman who did “man's work,” dressed as a man and sometimes called themselves “John Woodman” and Peg Wesson who could turn herself into a crow ... Tammy Younger (1753–1829) and Judy Rhines (1771–circa 1830), two women who practiced witchcraft in those days, became the subject of many stories.

One of these can be found in Percy MacKaye’s 1923 poem, Dogtown Common, in which Judy Rhines is portrayed as Younger's innocent niece. She falls in love with the minister, John Wharf, and when accused of witchcraft by the small-minded villagers of Annisquam, she throws herself off a rowan tree and dies.

So where the “Parting Path” splits at Whale's Jaw

The berry-pickers pass her hearth and tell

Old yarns of Tam the Witch, and what befell

Of weird ordeal and awe.

Young Judy Rhines, her niece, whose lips no

wildrose haw

Could match for redness, till they quivered pale

As leaf-ash when John Wharf, the minister,

First looked at her. [1]

Gabrielle and I began a kind of meditation on Judy Rhines, back in 2023, when I staged the poem at Windhover Performing Arts Center for the Gloucester 400+ city wide celebration. Gabrielle created the backdrop, a spectacular drawing of the Dogtown woods.

Gabrielle's drawing of the Dogtown woods.

The actual Judy Rhines didn't kill herself. The Judy Rhines of the poem is a figment of MacKaye's post-Victorian imagination. In The Resurrection of Judy Rhines, Gabrielle and I save her from this false history with our own ghost story, told in Gabrielle's drawings and a narrative text that we made up, in which rumors speculate about what became of her after she disappears.

“Word was, she climbed a tree and threw herself off. Or she just walked away. Nobody knew for sure. Later, she was seen in many forms … a little girl, a teenager, even a wild animal.”

The poem irked Gabrielle. She kept saying, “Those Annisquam people murdered that girl!”

Elder Zorab Coit (from Dogtown Common):

Bull o’ Bashan!

Who’s that awalkin’ side of [the minster — John Wharf?]

Not Judy Rhines? Not bringin’ here that goody

To meetin’! All creation won't stand that!

Mebbe, though, he’d let the Lord's damnation

Strike her right here in church. I wonder— would he? [2]

In the dramatic production of Dogtown Common that we staged at Windhover in 2023, each character was represented by a doll, which became like a witch's “familiar”.

We used dolls in Dogtown Common, which were like witches’ “familiars.”

For the current installation at the White-Ellery House, Gabrielle drew a picture on cardboard in which the dolls sacrifice the Judy Rhines doll on a piece of granite. This, in turn, triggered the current collaboration. We began to trade ideas and a story developed.

The sacrifice of Judy Rhines.

Our Own Legend: The Resurrection of Judy Rhines

We imagined scenarios based on different rumored sightings of Judy all over Dogtown. Gabrielle started a series of drawings, and as they developed, they took on meanings that left the Dogtown Common poem behind. Judy wanders into the woods, and the line between rumor and dream becomes ambiguous.

The Real Judy Rhines

As far as we know, Judy Rhines, herself, had little in common with the Judy Rhines of the poem, though she did practice witchcraft and, allegedly, prostitution. Beyond that, little is known about her. For Gabrielle and me, the installation became an adventure in mythmaking. Others made up stories about Judy Rhines. Why shouldn't we? In fact, there are a lot of stories about the denizens of Dogtown in the early 19th century. Many of them were collected by the editor of the Gloucester Times, Charles E. Mann, in his 1909 book, In the Heart of Cape Ann or the Story of Dogtown. [3]

Dogtown Lore

Originally known as The Commons, the wooded center of Cape Ann became “Dogtown” when, after the Revolution, the residents moved to the coast. The abandoned houses were taken over by people who, for one reason or another, didn't fit in. They were “unstable,” couldn't hold down a job, ex-slaves, or women without families. Such women had no respectable way of making a living, and there were many widows after the war.

There were berry-pickers, subsistence farmers, prostitutes, and witches in Dogtown, a place to go for sex, drink and fortune telling. And there were rumors about what went on up there, mostly about the witches. Judy was not the most storied among them.

Tammy Younger was known as the Queen of the Witches. She used the threat of a curse to extort fish and produce from anyone foolish enough to pass her house on Fox Hill. At night, people snuck up to Tammy's to have their fortunes told. Even after she died, people feared her powers. Mr. Hodgkins built her coffin, but he wouldn't keep it in his house while he slept — because of the “evil” in it.

The story about Peg Wesson was that she threatened some soldiers. Later, they thought they saw her circling the sky in the form of a crow. One of them shot it down with a silver button — the only metal known to pierce a witch's flesh. At that same moment, it was said, Peg collapsed, and a doctor that tended to her pulled a silver button out of her leg.

Where women were once persecuted for being witches, these women proclaimed it. Marginalized as they were, witchcraft was one way that they could assert their power. And not only did they survive, they lived on in the imaginations of their Gloucester neighbors.

Gloucester Outlier Town

Mythmaking and why legends grow is something Gabrielle and I thought about as we imagined Judy Rhine’s walkabout. If stories mirror the storytellers, what did Gloucester people find of themselves in Dogtown lore? From the beginning, Gloucester was an outlier among Puritan farm towns of Massachusetts Bay. According to historian James B Connolly, the first Gloucester settlers were forced to leave Plymouth over a religious dispute. “The insurgent ones were rounded up by Governor Bradford and told to betake themselves quickly to some distant part of the colony.”[4] And so, they found Gloucester. Its rocky soil was not good for farming. It became something of a way-faring town and a little wild. It developed differently from the more settled communities on the coast, until fishing eventually shaped its character, which has always been ... all its own.

Let's call Dogtown, Gloucester's “wild interior,” a reflection of its struggles, its libido, its peculiarity. Something of the intractable difference in Tammy Younger or Old Ruth resides here—or, for that matter, in Charles Olson—who famously portrayed James Merry wrestling with a bull in Dogtown, until it killed him.

Collaborating

Gabrielle and I had different perspectives on the Judy Rhines story, but they worked together. Gabrielle saw Judy as a fighter. She's a witch and also a pissed off teenager. It was Gabrielle's idea that a beast should attack Judy, who strangles it. She skins it with her teeth and takes its power (figure 4).

“After blood-stained clothing was found, it was reported that Judy was killed by a beast. But in a fit of rage, she strangled it, gutted and skinned it with her teeth. Then she cooked it. She was stuffed with meat and took a nap.”

She put on the skin of a beast.

In imagining Judy's walkabout, Gabrielle mapped out the route in her mind, from the high land by the harbor to Raccoon Ledges, the plateau where Judy gorges on blueberries, and Whales Jaw. And something subjective from Gabrielle's not altogether New England background seeped into her dream of the woods. That she is herself a twin with Russian ancestors might explain the pair of Russian twins who show up and help Judy Rhines cover Whale's Jaw with graffiti.

“Up at Whale's Jaw, a boy and a girl seemed to come out of nowhere. ‘We're not from here,’ the girl said. They were twins. The boy sat and watched as Judy and the girl graffitied the entire surface of the rock. The girl was so excited that she ran away to St. Petersburg. She became an artist and even slept with Dostoevsky (once)”.

Judy Rhines at Whale's Jaw.

As for my perspective, I was influenced by the dramatic conflict in the Dogtown Common poem, as I staged it at Windhover. Judy Rhines becomes emotionally isolated from her Puritan community. At the end, when the poem has Judy Rhines throw herself off a rowan tree, I had her simply walk away. Frankly, she'd had it! I was interested in how someone breaks out of their own prison, and especially the prison of Puritanism, which in many ways still defines American culture. What kind of world opens to you?

Wandering in the woods, Judy moves from lament to rage, animal savagery, a nap, seclusion, revenge, reconciliation, healing, and transformation, in a kind of evolving state of wonder.

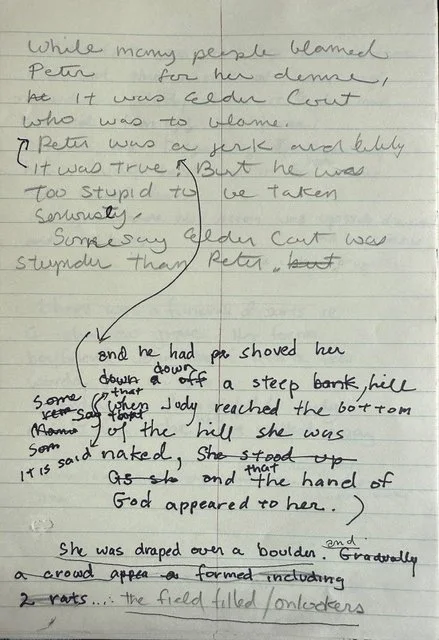

In our collaboration, Gabrielle would make a drawing, and I would come over to her studio to look at it. We would discuss its implications and where they led. We'd talk on the phone, and she'd text me another drawing. One night, Gabrielle woke up with a jumble of ideas that became a kind of breakthrough. She immediately wrote them down on a piece of paper. Here are her notes:

Gabrielle's notes.

Gabrielle was meticulous about organizing the drawings into portfolios, envelopes, and boxes, along with props, mostly animal figures. And jars to lean things against.

She made endless drawings of feral dogs—and other drawings she didn't necessarily know what to do with, such as a set of contemporary people smoking cigarettes. We presented what we had to friends in little showings. I read the text, and Gabriele set up the dioramas. It was a way to try out the narrative movement. Like a play. I thought we should take it on the road ...

At Raccoon Ledge, she lived in a cave.

Another Wrinkle: the beginning of the end (of Judy Rhines)

A Radio Mystery

At some point, we got the idea to haunt The Resurrection of Judy Rhines installation with something ghostly echoing through the halls of the White-Ellery House. So, I wrote an old-fashioned radio broadcast called the beginning of the end (of Judy Rhines). It's a mystery about how Judy Rhines came to witchcraft, and it takes place in the 1940's. Judy's a secretary in Boston, until, one day, she loses her job ... She wanders through the city that seems to be erasing her, until she begins to fight back. We made a recording starring Phoebe Potts, Sarah Hickler, Michael McNamara, and Evan Lurie, who provided the music. Michael Lamarche was sound engineer and editor, and I directed. Then we set up a little theater in the White-Ellery House storeroom with an old radio and a drawing by Gabrielle of the moment in the story when Judy returns home to find a strange woman sleeping in her bed. There's a lot I could say about it, but you will find out for yourself if you visit us in the White-Ellery House in August.

From the beginning of the end (of Judy Rhines), a radio mystery: Judy comes home to find a strange woman sleeping in her bed.

The White-Ellery House

When we first set up the drawings in the rooms of the White-Ellery House, they didn't seem to gel. Something was missing. So, Gabrielle began to add layers. This is a process in the theater that I love, when the production starts to develop in relationship to the setting, and the one influences the other.

Gabrielle at work.

We were getting near the final stage: growing the installation into the space. We spent quite a few hours in the rooms in the middle of the winter. Our toes were freezing, but that was one of our most fun times working together. Gabrielle was full of surprises. For instance, she set up her “smokers” around the diorama of the sacrifice of Judy Rhines. They added a hilarious irony, puffing on cigarettes and gazing into the terrible past.

Conclusion

Working on our own Judy Rhines legend gave Gabe and me a way to reflect on our feelings about Gloucester, a place that we love. I'd say The Resurrection of Judy Rhines also became a kind of meditation on freedom. Not just how to attain it, but what is it? Where does freedom really lie?

Judy Rhines finds a deeper relationship with existence itself, wandering in the Dogtown woods, which turns out to be bigger than her community and bigger than herself. And in this, she discovers a kind of freedom she never would have imagine—from hurt, small-mindedness and conformity. We all face this, don't we, in our own walkabout ... in the Dogtown woods...?

NOTES

1. Percy MacKaye, Dogtown Common, J. J. Little & Ives Company, New York, 1921.

2. Percy MacKaye, Dogtown Common, (Ibid).

3. Charles E Mann, In the Heart of Cape Ann or the Story of Dogtown, Proctor Bros Publishers, Gloucester, Ma, 1909.

4. James B. Connolly, The Port of Gloucester, Doubleday, Doran, and Co, 1940.

Peter Littlefield is a writer/director. His theater collaborations include Peter Pan for Fisher Center at Bard and Handel's Partenope at the English National Opera. His latest film, god's mom, is an interpretation of Revelations. This is his second project with Gabrielle Barzaghi. He teaches playwriting at the Gloucester Writers Center.

Photo credit: Jerry Russo

Gabrielle Barzaghi is a visual artist whose imagery is evocative of places just beyond the edge of normal experience, and has an often otherworldly sensibility about the nature of time and being. Her work is in public and private collections, including the Cape Ann Museum.

The Harbor

Your flesh is a fathom of brine

& a layer of light

always beckoning