Cape Ann’s Vernal Ponds

By Paul Erickson, COSMOS Science Contributor

Revised edition, originally published March 2022

One of Cape Ann’s many vernal ponds, mid-March.

©Paul Erickson

You’re a salamander. A spotted salamander in a forest on Cape Ann. Spring has arrived and you’ve been sheltered underground in an abandoned mole tunnel for the last eleven months.

Now, with warming air and soil, you creep out of your hideout on a rainy night. Then, under the cover of darkness, you begin a quarter-mile migration to a small vernal pond in a woodland beside Route 127. There, you join other breeding spotted salamanders among sunken leaves at the bottom of the pond. All around you life is waking up. Wood frogs quack. Fairy shrimp—small aquatic crustaceans—perform an elegant water ballet.

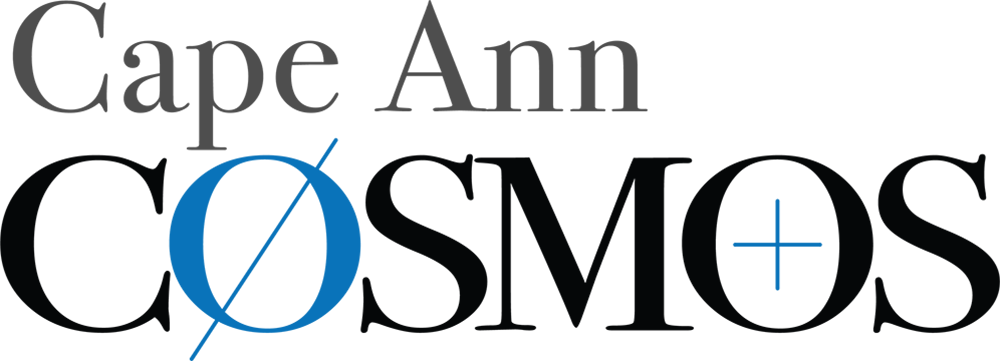

During the next few weeks, female salamanders attach fertilized egg masses to partially sunken branches and twigs. When the breeding activity is complete, you and your pond-mates will leave the pond and return to the underworld of the forest floor to feast on earthworms, slugs, and snails.

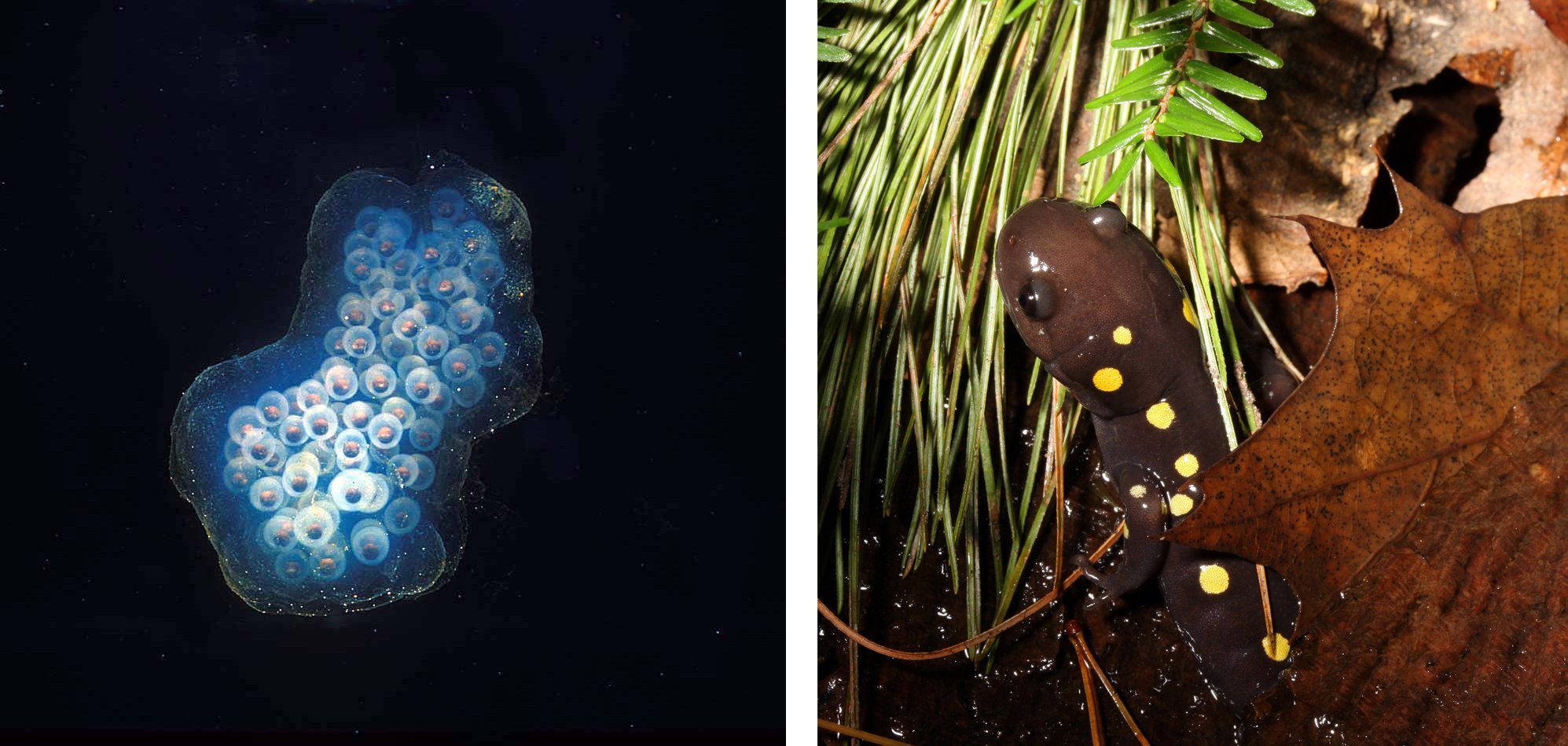

Meanwhile, life in the Cape Ann breeding pond continues to develop. Salamander eggs hatch into aquatic, tadpole-like larvae. If the swimming larvae survive attacks by lurking dragonfly larvae and other predators, they grow into juvenile salamanders. Usually by late summer, the juveniles, showing off their new, bright yellow spots, leave what’s left of their evaporating freshwater sea and migrate near and far to seek out their own shelters under logs and in rodent burrows.

In springs to come, the new generation of spotted salamanders will migrate to vernal ponds—including the ones where they were born.

Vernal Pond Conservation

Being a salamander fanatic and a science writer in search of a story angle, I was thrilled to learn about Cape Ann’s own group of vernal pond enthusiasts—the Cape Ann Vernal Pond Team (capeannvernalpondteam.org). Team founder, Rick Roth, kindly granted COSMOS an interview during his busy spring salamander season. Here’s what he shared with us:

Spotted salamander, eggs and hatched. ©Paul Erickson

Paul: Why did you found the Vernal Pond Team?

Rick: Thirty-two years ago, on a night in early spring, a guy who knew I was into creepy crawlies took me to a vernal pond. The first things I saw in the water were fairy shrimp. They were fascinating.

So I’m watching these fairy shrimp with my face close to the pond’s surface and this five-inch-long spotted salamander startled me when it surfaced for air. I thought this dark-charcoal-grey salamander with bright yellow spots was quite a spectacle.

As it turned out, the guy who took me to the pond told me that someone from Essex County Greenbelt was going to do a public talk about these ponds. At the presentation, I learned how people certify these amazing habitats. Before long I got together with several interested people and formed a non-profit corporation dedicated to conservation.

Rick Roth

Paul: Please tell us about your field trips.

Rick: We do everything we can for the public for free. That includes running guided field trips to vernal ponds. I lose money at this.

Paul: How can people connect with your group?

Rick: If you would like to go on a free guided field trip to one of Cape Ann’s vernal ponds, contact the Vernal Pond Team at cavpt@yahoo.com. Then click on the word “CONTACT” at the bottom of the web page. We’ll notify you, typically on very short notice, when the salamanders have arrived, and it’s time for a nighttime adventure. And of course you should check out our website: capeannvernalpondteam.org.

Paul: Do you ever give talks for the public?

Rick: Yes. The Cape Ann Vernal Ponds team will be hosting three regional events, in Manchester, Lynn, and Essex. Everyone welcome!

Paul: How do you certify vernal ponds?

Rick: Certifying ponds with the Massachusetts Division of Fish and Wildlife / Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP) is how we protect them. That requires photographing ponds as proven salamander breeding habitats by documenting at least six egg masses in each one.

Paul: How many vernal ponds have you found on Cape Ann?

Rick: We have certified over 300 of them on Cape Ann and elsewhere, and there’s more to go.

Paul: How big is a vernal pond?

Rick: On Cape Ann, a small pond can be 20 feet in diameter or smaller. Most of them form where there are natural depressions in the ground. Some were formed a long time ago in small backyard quarries that quarry workers would cut out and sell the granite for extra income. Then year after year, decaying leaf litter accumulated in backyard quarries, turning them into complex vernal pond habitats. As for large vernal ponds, one on Cape Ann is 500 feet in diameter.

Did You Know?

Vernal ponds are also known as ephemeral pools and spring pools. Typically they fill with water and snowmelt in autumn, winter, and spring. They remain ponded through the spring and early summer and dry up completely by the middle or end of summer every year or at least every few years.

Temporary vernal ponds periodically dry up and therefore cannot support salamander-eating fish populations. Bigger ponds and quarries on Cape Ann hold water all year long and can provide habitats for predatory fish. Therefore you won’t find salamanders in them.

Depending upon where you live, these other organizations will help you learn about and explore vernal ponds: